The release this past month of Beck's Modern Guilt has gotten me to thinking about the albums that I love that I can't claim as great. Last year, I wrote on here about Joni Mitchell's The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, which I think has to be the epitome of this type of thing - an album that I could find dozens of reasons to dislike, except that so much is done right on the album and drawn to it over and over again. Artists all the time make albums that are mediocre with a few good songs sticking out, but this is something different - albums that are made to be expansive and brilliant wind up tripping on their own ambitions. Still, I love those grand amibitions so much, I keep trying and trying to love the album as much as the artist clearly did. Mostly it doesn't work, but what comes out of it is something that makes you happy you tried.

The release this past month of Beck's Modern Guilt has gotten me to thinking about the albums that I love that I can't claim as great. Last year, I wrote on here about Joni Mitchell's The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, which I think has to be the epitome of this type of thing - an album that I could find dozens of reasons to dislike, except that so much is done right on the album and drawn to it over and over again. Artists all the time make albums that are mediocre with a few good songs sticking out, but this is something different - albums that are made to be expansive and brilliant wind up tripping on their own ambitions. Still, I love those grand amibitions so much, I keep trying and trying to love the album as much as the artist clearly did. Mostly it doesn't work, but what comes out of it is something that makes you happy you tried.Once, Roger Ebert wrote about The Darjeeling Limited (a movie I didn't like at all), "Why do we have to be the cops and enforce a narrow range of movie requirements?" I identify with that statement quite a bit. It gets to be an exercise for critics, wanting to keep up an aura of crumudgeonness - of being difficult to please and having discerning tastes - to not discuss what good is in a movie or album or book but to instead make sure s/he is on top of pointing out a work's flaws. That's fine - flaws need to be discussed too - but perhaps tougher is to engage with a work whose flaws are obvious and acknowledge what draws you in about it. Since Beck's Modern Guilt is exactly this type of record, here are two others that fit that definition, and my ever expanding thoughts on that damn Joni Mitchell album I can't stop thinking about.

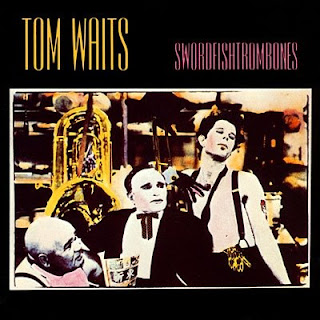

Swordfishtrombones Tom Waits

Ask ten Tom Waits fans to pick the album that typifies Tom Waits to then, and they'll likely give you ten different answers - or, at the very least, 6 or 7 answers, with many of them repeating the title Rain Dogs. In the mid-70's, Tom Waits stopped making the sort of back alley jazz records and got into work that was darker and more tortured. By the mid-80's, he decided much of that was still too melodic, and made Swordfishtrombones, which begins in "Under Ground" like a small child banging on a xylophone, accompanied by a barking old man.

This was the album that would enable Rain Dogs, and, really, establish the weirdness that has remained Waits's backbone. For me, my own answer as a Waits fan to what his best album is would be Bone Machine, the astonishing 1990 album that sounds like one miraculous round trip to hell and back. Getting into Tom Waits now, as people cranky enough who are my age sometimes do, I wouldn't expect that Swordfishtrombones would be the record they'd gravitate towards - full of bangs on a kettle drum, off-key blows in a bassoon, screaming. In the track "Shore Leave," the title is sung cryptically towards the end of the song in a way that sounds like a baby spitting out its food. By the time you start hearing circus music during "Dave The Butcher," you're not even sure Waits knew he was supposed to be a musician.

Of course this is Waits's charm and it seems most charming to the cognizenti when he's at his most baffling - or at least, so they say. People's favorite Tom Waits' songs also tend to be the more melodic ones, and understandably so (how do you even remember the other ones?). The album is tough - but it's not without comprehension, revelation, and often beauty. No other artist makes records that can be ugly and silly and critical and light. When, in "Frank's Wild Years," Waits delivers a disaffected monologue to an organ about a man, his wife, who was "a used piece of jet trash, made good bloody mary's, and kept her mouth shut most of the time," it's something so wild and unhappy it winds up levitating on its very unlikelihood of causing a smile. If you make it that far, the album, without a doubt, wins you over - enough so that in the straight, beautiful numbers like "In The Neighborhood" or the jazz composition "Rainbirds," you truly believe in what Waits is doing, even if it took a lot of ignoring disbelief to get there.

29 Ryan Adams

The backstory behind 29 is that Ryan Adams had to shelve it for a while - it did, after all, come out when he was 31, his final of three albums released in 2005. Strategically it makes sense - 29, unique in Adams' catalog anyway, definitely didn't fit with his more direct, pop-oriented songs of Gold and Love Is Hell, and had at least a comrade of sorts in the countrified drunkenness of Cold Roses and Jacksonville City Nights, Adams' other 2005 releases. It was deemed too weird and obscure, but as the bass drum beats and guitar blazes a sound right out of the Grateful Dead's "Truckin" on the title track, it's something else - a declaration of survival. In the track, Adams muses "I should've died 100,000 times" and "Most of my friends are married and making them babies/ To most of them I've already died." He recounts bar fights, arrests, close calls, drug use, and even his dead dog's pile of bones and then roars on his way - it's obscure enough, I suppose, but it's also a thrill. Coupled with its following song, "Strawberry Wine," which has a softer Adams musing "Don't spend too much time on the other side/ let the daylight in," Adams imagines the side of his 29 years if he hadn't survived, and that makes this, really, a concept from start to finish about the luck of the surviving - even a manual of sorts.

Adams has long been criticized as being a machine that cranks out songs rather than an album artist, but 29 is the antithesis - a full record not that concerned with the song to song individuality. That's the strongest thing about 29, but it also isn't fulfilled. Though its middle, sad songs "Night Birds" and "Blue Sky Blues" are terrific, they're followed by the terrific, what-drives-me ramble "Carolina Rain" and then left unfulfilled by what should be the conceptual meat of the record - a bla love song "Starlite Diner," and "The Sadness," a fight with depression re-imagined as a bullfight. The truth is neither of the songs work, and they disrupt Adams' conceptual daring.

The record picks back up with "Elizabeth, You Were Born To Play That Part," as emotional a song as Adams has ever written with its collision of two absolutely gorgeous melodies. However, the heartbreak seems isolated. "Voices" concludes the record, and it's like a postmodern folk song - all deadly pleas and emotional coos so trenchant you barely notice there's only an acoustic guitar playing. This song should connect 29's ends of survival - with its "Don't you listen to the voices" center, it's the hope that makes his good luck story of "29" possible - but it doesn't, it merely ends the album respectably. That all leaves 29 mostly unfulfilled, but still - there are times I can't sleep at night and "Voices" is the song I want to hear. There are times I drive in the rain and "Elizabeth..." is the song I want to hear. There are times I find myself amazed to be who I am and "29" will pop up - it's amazing that an album can call forth that sense of identification and still, not fully, work.

The Hissing of Summer Lawns Joni Mitchell

What's left for me to say about this record? To call songs like "In France They Kiss On Mainstreet," "The Jungle Line" and "Don't Interrupt The Sorrow" tuneless would absolutely be right. But they also come at a speed of ideas and criticism that is its own bit of intoxication. Last year's Grammy-winning River, the Mitchell tribute albumy by Herbie Hancock, featured "The Jungle Line" turned into a spoken-word jazz piece, and maybe that's the right forum for it - not the moog-sampling wander from painted jungle flowers to crossing the Brooklyn Bridge that it has. As it is, it, like the majority of the songs on the record, are hard to know and hard to like. Sean Nelson, the eloquent writer for the 33 1/3 series, in writing about Mitchell's Court and Spark called out Mitchell on Hissing for losing all sense of compassion and empathy - this is Mitchell at her most disdainful. Her opening image in "Mainstreet" is of "under neon a signs/ a girl was in bloom/ and a woman was fading/ in a suburban room." That might be the nicest comparison she makes on the record - she sees women as chained to Ethiopian walls, imagines Scarlett O'Hara wandering Times Square for porn, sees nagging wives ruining their husbands' lives, finds them unable to speak up to save their lives.

The truth is, as hard of an edge as these songs leave you with, I've never disliked them, not any of them, even "Edith and the Kingpin," which is, I think, a waste of a song. "Don't Interrupt The Sorrow" calls forth the history of women suffering and surviving only to be given the platitude "Bring that bottle over here and I'll pad your purse" - why not be angry? Its second half, too, has a perfect run - a man reminisces angrily on "Harry's House/ Centerpiece" and the result is experimental and beautiful. She dissects a bad local band in "The Boho Dance" rather dispicably as "just another hard time band/ with Negro affectations," but winds up really making a case for musicians needing to be true to who they are.

What keeps me coming back to Hissing is what has to be its strangest song - and Mitchell's strangest, for that matter. "Shadows And Light" was the first song I objected to on the record, and with its long, slow, drawn out keyboard as its only instrumentation, why wouldn't I? In her first mainstream negative review, Steven Holden of Rolling Stone wrote that the song sounded like "a long, solemn fart." But where the songs of Hissing are angry, "Shadows and Light" is lead by a synthesizer that accepts vicious dichotomies for what they are - stands in acceptance of them. "Hostage smiles on presidents, freedom scribbled on the subway," she sings to silence, and I have to think, to all things there are good and bad. We've given women - given ourselves - freedom and wound up bound to it. How do we reconcile the two? It's an effort to get there, but Hissing to me retains its fascination because it's, ultimately, just worth it.

Modern Guilt Beck

Beck has to be upset something fierce these days - the songs in Modern Guilt are pulled out of their straight malaise by dancy production of Danger Mouse, but there's not doubt of what he's feeling. "If I wake up and see my maker coming," he sings in the opening number, "Orphans," "We'll drag the streets with the baggage of longing." He drags the album with the baggage of longing - each song seems to be about how he no longer recognizes the world around him, and climaxes with Beck contemplating leaping into a volcano.

I should, in all honesty, truly identify with this record - I find myself baffled by modern culture constantly, and I think in 2006's magnificent The Information, Beck did just that - imagined a world with dead cellphones, drowned out by elevator music, and adrift with the strangeness of the world around him. The truth is, Beck's previous albums are the best reason to move forward with Modern Guilt anyway - knowing the winning streak he's been on. My theory with Beck has long been that 2002's classic Sea Change, full of such overwhelming sadness, freed Beck to make the music he wanted to - the far jauntier Guero and The Information along with Change are truly Beck's fullest, most inspiring work.

Modern Guilt is along that vein but is simply not as good because there is no movement - Beck's malaise traps you in the record and suffocates it with dance rhythms that feel mostly stapled on. A song like "Replica" makes great use with intensely overdone beats of creating a sonic landscape that seems impossible to penetrate, but most of the record does so without as much sense of consciousness.

But that consciousness still lingers and infects. The truth is I didn't care much about Beck when I was supposed to - Odelay and Midnite Vultures seemed like a lot of danc-y hoohah about nothing, and even when I liked a song I didn't care to go much further. Modern Guilt has so much to it, by contrast. "Orphans" is a great song, and so is "Volcano" (of that titular volcano Beck can't decide to jump into), and even at one note, a record about modern contempt and malaise is a stronger note than virtually all other albums in release. The truth is, the best thing of a record about malaise and contempt is that you feel it some yourself - you yearn for the release in songs like the crunchy rocker "Soul of A Man." That may be as effective as it is frustrating.

No comments:

Post a Comment