Ethan's spot for criticism, writings, and thoughts in general.

In The Confessions of Max Tivoli, what seems like a gimmick takes on the air of great sympathy and understanding. Its protagonist, born with a foreknowledge of his death by simple addition, is born an old man aging backwards. We view him meeting his best friend with the face of a 54-year-old, falling in love with a girl his age while secretly sleeping with her mother (he does, after all, appear to be even older than she), getting the girl when they both coincide at the right age, and then, finally, pretending to be the same age as her son some decade and a half after she leaves him. Beyond requiring the most suspended of suspended disbelief, this concept seems hokey and awkward at fist glance – ages backwards? What are we supposed to learn, that age is a state of mind? Is this a Robin Williams starring vehicle in disguise?

There is simply nothing to prepare you for the actual text in the novel, which, both directly and indirectly, seems a modern incarnation of Lolita, another novel whose startlingly beautiful language takes a sticky concept and turns it into the ultimate meditation on love and life. I do not mean to say Andrew Sean Greer has the talent of Vladimir Nabokov (although, who’s to say, this is only his second novel). There is not a hint of preciousness in the design, not a second of cozying into the subject, not a single person who rises above his/her circumstances to learn an important lesson on the universality of humanity. No, that responsibility is ours, and the lyricism of the backwards man-boy does teach us invaluable truths about love, about self, about time, and about the inevitability of aging – as it is here, careening like a car crash you are powerless to control, the process that takes Max back in time propels us and confronts us with the inevitability, the uncontrollably finite process of time and age.

Max, being (mostly) the only person aware of his predicament is certainly a character locked into a sense of insular logic – being the only person having to live in his body, with his choices, it becomes a certain inevitability he’ll jettison the “life” of Max Tivoli on each reappearance of Alice, the girl he remarks towards the end of the novel he’s not sure if he ever really knew. Mid novel, he “becomes” his father, Asger Van Dalen (rechristened

To an extent, this can be read as a metaphor for love in general – the couple is given less than a decade of happiness before the moment she says to him, “I don’t know who you are.” It’s true she doesn’t, his identity is a lie, but the love is as strong as ever. Much like Lolita, the protagonist gets his woman for a time, but in truth never really has her, her affections somewhere else, and her need for Asger never coming close to resemble the intensity of feeling Max has for her.

It’s hard to tell when the book first sideswipes you and has you in its clutches. Perhaps it’s at the end of its first section, upon the realization that Sammy, the 12-year-old a now-58-year-old Max shares a room with, is actually his son. What it does is make the story, for perhaps the first time, full of possibility. You were willing to write off a character who either seems like he’ll be Simon Birch (that is, chirpy and sentimental) or else the Elephant Man (and invoke “you poor thing!” syndrome). The son gives you the sense that this man may have had a full life, entering and backing away from real interaction with the world, conquering his affliction occasionally, falling victim to its implications in others.

In that sense, what becomes the most sympathetic aspect of Max is, in its eloquent precision, his isolation. This isolation may be justified – he can’t exactly proclaim his condition to the world. Still, as a 17-year-old awkward in his skin, it barely matters that that skin is a 53-year-old’s – we all understand the sense of feeling a foreigner in your own body, skeptical of the way people view you and the way you view yourself.

Which is to say Andrew Sean Greer, a lyricist if ever there was one, follows precisely the axiom of great writing: take the specific, make it universal. Certainly the story of a Max, in love with an

The answers to these questions are great answers, of course, as any good novel must be fully aware of the appeal of their smallest tidbits. The final fourth of the novel, a section of careening intensity is so full of themes and elements you barely knew had overwhelmed your every sense – Max’s lifelong friendship with Hughie, the absence of his mother, the castrating effect of time on his body (as a 12-year-old, he notices, resigned, he just can’t get the thing to work like it used to), the accidental discovery of Alice’s whereabouts, Max’s hypnotic conversation with her newest ex-husband, the end of Hughie, and a final, sweet resolution of the whole crew – a late night cry and kiss goodnight from a torn up Alice.

What makes reading and absorbing these details such an overwhelming and moving experience, I think, is that concept that seemed cumbersome and untenable in the extreme to begin with, the obstinately backwards movement of time in a culture confined to a linear existence. Rarely in a novel – in absence of a terminal disease (and I’m happy for every time one is absent in a novel) – are we so swiftly reminded of the mortality of our protagonist. Even at 12, we know his years are even more finite than that because this trajectory of time, even more than an age-related dementia, will literally turn Max into a baby. In their magnificent final moments together, Hughie begs for a solitary existence with Max, saying he alone understands Max’s fear of dying as a helpless baby, and he alone is his answer to it. We know he’s right – Max, we’re certain, has no possible way of telling Alice or Sammy of his condition, and it’s a moment that clues us into the mental singularity of a man forced to live his life in total isolation from the world.

Was Hughie simply acting out a lifelong crush on Max? That reading is possible, I’m afraid, and in those final sections of the last quarter of the book, you’re thrust into an unenviable position as a writer – that is, the position to dismiss Hughie’s mostly human behaviors as long overdue puppy love. I choose not to read it this way, although I admit that such a non-reading is an arbitrary choice. Hughie, a homosexual in the beginning of the 20th century, and Max are equal foreigners in their bodies and their worlds, and Max draws this parallel frequently. I read Hughie’s love for Max comes from a bond of understanding, of being the only two people alive that, without judgment, accept each other as they are. Indeed, Hughie’s secret is as antisocial as Max’s – unmoved by the death of his son and in a marriage that’s more annoyance than matrimony, Hughie is simply a man trying to find any way to make it through his days. With Max to look out for, he has someone to feel superior to (he does, after all, have it easier), and thus, accepted by.

I searched for reviews of The Confessions of Max Tivoli after I completed the book, and, dazed from the emotional wallop of its final quarter, and overwhelmed by its parallels to Lolita (more in a moment), I was surprised to hear the analysis, “beautifully written, but without anything meaningful to say on love and life.” I couldn’t disagree more. It may be not so noteworthy to say that love is all there is to live for, and that it is eternal – so, maybe there isn’t that much left to say on love – but as for life, I think

What it means is that the experience of good writing on your existence is a profound communicator – Max, who could not approach the things that mattered to him during life did find them after his death, either by a theoretical understanding of whatever Alice makes of these journal entries or, if Max is correct in his final pages, by having his 1941 necklace returned to her. He also lives on by the work of his son, perhaps even inspiring and causing the work of his song. It means that Sammy was so profoundly moved by what he read, he worked his life to publish it. This simple sentence after the completion of the events of the novel says that marking your existence on this planet, you make your mark by being true and creating proof of your existence. In another echo of Lolita, we’re told of what the power of writing will allow you to forgive. Max is a far less treacherous human being than Humbert Humbert, but he felt no less isolated, and, in truth, he’s not very much less eloquent.

Why Lolita, you ask? Like Lolita, Max gets the girl for a while, only to have her taken away by something he should’ve seen just under his nose. Like Lolita, he meets her briefly before one or both of the main characters’ deaths. Like Lolita, the “transcripts” we’re given are posthumous of the main character, and the fates of the other remaining characters told by an ominous outside source. Like Lolita, the character’s first sexual encounter is told in poetic non-specifics. Like Lolita, you forgive unforgiveable acts because you love the voice of the person speaking them.

It’s amazing that a novel with a ludicrous concept could leave such an indelible impression about the nature of people, the truths of existence, and the importance of expressing them. It’s amazing that it could still do this in the best way a novel can, by sideswiping you with utterly absorbing characters in a fully spellbinding narrative flow. The Confessions of Max Tivoli as a title is a sort of everyman journal entry type of banality, and that, in truth, could be the case – this is simply a man we’re presented with, with elements of his mortality and purpose apotheosized to the order of highest importance. In essence, they remind us why those elements are of the highest importance to us.

The release this past month of Beck's Modern Guilt has gotten me to thinking about the albums that I love that I can't claim as great. Last year, I wrote on here about Joni Mitchell's The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, which I think has to be the epitome of this type of thing - an album that I could find dozens of reasons to dislike, except that so much is done right on the album and drawn to it over and over again. Artists all the time make albums that are mediocre with a few good songs sticking out, but this is something different - albums that are made to be expansive and brilliant wind up tripping on their own ambitions. Still, I love those grand amibitions so much, I keep trying and trying to love the album as much as the artist clearly did. Mostly it doesn't work, but what comes out of it is something that makes you happy you tried.

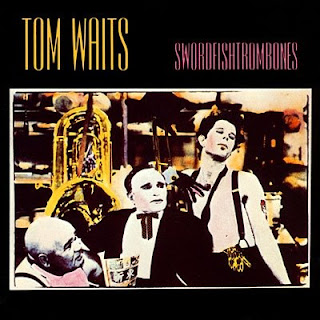

The release this past month of Beck's Modern Guilt has gotten me to thinking about the albums that I love that I can't claim as great. Last year, I wrote on here about Joni Mitchell's The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, which I think has to be the epitome of this type of thing - an album that I could find dozens of reasons to dislike, except that so much is done right on the album and drawn to it over and over again. Artists all the time make albums that are mediocre with a few good songs sticking out, but this is something different - albums that are made to be expansive and brilliant wind up tripping on their own ambitions. Still, I love those grand amibitions so much, I keep trying and trying to love the album as much as the artist clearly did. Mostly it doesn't work, but what comes out of it is something that makes you happy you tried.Ask ten Tom Waits fans to pick the album that typifies Tom Waits to then, and they'll likely give you ten different answers - or, at the very least, 6 or 7 answers, with many of them repeating the title Rain Dogs. In the mid-70's, Tom Waits stopped making the sort of back alley jazz records and got into work that was darker and more tortured. By the mid-80's, he decided much of that was still too melodic, and made Swordfishtrombones, which begins in "Under Ground" like a small child banging on a xylophone, accompanied by a barking old man.

This was the album that would enable Rain Dogs, and, really, establish the weirdness that has remained Waits's backbone. For me, my own answer as a Waits fan to what his best album is would be Bone Machine, the astonishing 1990 album that sounds like one miraculous round trip to hell and back. Getting into Tom Waits now, as people cranky enough who are my age sometimes do, I wouldn't expect that Swordfishtrombones would be the record they'd gravitate towards - full of bangs on a kettle drum, off-key blows in a bassoon, screaming. In the track "Shore Leave," the title is sung cryptically towards the end of the song in a way that sounds like a baby spitting out its food. By the time you start hearing circus music during "Dave The Butcher," you're not even sure Waits knew he was supposed to be a musician.

Of course this is Waits's charm and it seems most charming to the cognizenti when he's at his most baffling - or at least, so they say. People's favorite Tom Waits' songs also tend to be the more melodic ones, and understandably so (how do you even remember the other ones?). The album is tough - but it's not without comprehension, revelation, and often beauty. No other artist makes records that can be ugly and silly and critical and light. When, in "Frank's Wild Years," Waits delivers a disaffected monologue to an organ about a man, his wife, who was "a used piece of jet trash, made good bloody mary's, and kept her mouth shut most of the time," it's something so wild and unhappy it winds up levitating on its very unlikelihood of causing a smile. If you make it that far, the album, without a doubt, wins you over - enough so that in the straight, beautiful numbers like "In The Neighborhood" or the jazz composition "Rainbirds," you truly believe in what Waits is doing, even if it took a lot of ignoring disbelief to get there.

29 Ryan Adams

The backstory behind 29 is that Ryan Adams had to shelve it for a while - it did, after all, come out when he was 31, his final of three albums released in 2005. Strategically it makes sense - 29, unique in Adams' catalog anyway, definitely didn't fit with his more direct, pop-oriented songs of Gold and Love Is Hell, and had at least a comrade of sorts in the countrified drunkenness of Cold Roses and Jacksonville City Nights, Adams' other 2005 releases. It was deemed too weird and obscure, but as the bass drum beats and guitar blazes a sound right out of the Grateful Dead's "Truckin" on the title track, it's something else - a declaration of survival. In the track, Adams muses "I should've died 100,000 times" and "Most of my friends are married and making them babies/ To most of them I've already died." He recounts bar fights, arrests, close calls, drug use, and even his dead dog's pile of bones and then roars on his way - it's obscure enough, I suppose, but it's also a thrill. Coupled with its following song, "Strawberry Wine," which has a softer Adams musing "Don't spend too much time on the other side/ let the daylight in," Adams imagines the side of his 29 years if he hadn't survived, and that makes this, really, a concept from start to finish about the luck of the surviving - even a manual of sorts.

Adams has long been criticized as being a machine that cranks out songs rather than an album artist, but 29 is the antithesis - a full record not that concerned with the song to song individuality. That's the strongest thing about 29, but it also isn't fulfilled. Though its middle, sad songs "Night Birds" and "Blue Sky Blues" are terrific, they're followed by the terrific, what-drives-me ramble "Carolina Rain" and then left unfulfilled by what should be the conceptual meat of the record - a bla love song "Starlite Diner," and "The Sadness," a fight with depression re-imagined as a bullfight. The truth is neither of the songs work, and they disrupt Adams' conceptual daring.

The record picks back up with "Elizabeth, You Were Born To Play That Part," as emotional a song as Adams has ever written with its collision of two absolutely gorgeous melodies. However, the heartbreak seems isolated. "Voices" concludes the record, and it's like a postmodern folk song - all deadly pleas and emotional coos so trenchant you barely notice there's only an acoustic guitar playing. This song should connect 29's ends of survival - with its "Don't you listen to the voices" center, it's the hope that makes his good luck story of "29" possible - but it doesn't, it merely ends the album respectably. That all leaves 29 mostly unfulfilled, but still - there are times I can't sleep at night and "Voices" is the song I want to hear. There are times I drive in the rain and "Elizabeth..." is the song I want to hear. There are times I find myself amazed to be who I am and "29" will pop up - it's amazing that an album can call forth that sense of identification and still, not fully, work.

The Hissing of Summer Lawns Joni Mitchell

What's left for me to say about this record? To call songs like "In France They Kiss On Mainstreet," "The Jungle Line" and "Don't Interrupt The Sorrow" tuneless would absolutely be right. But they also come at a speed of ideas and criticism that is its own bit of intoxication. Last year's Grammy-winning River, the Mitchell tribute albumy by Herbie Hancock, featured "The Jungle Line" turned into a spoken-word jazz piece, and maybe that's the right forum for it - not the moog-sampling wander from painted jungle flowers to crossing the Brooklyn Bridge that it has. As it is, it, like the majority of the songs on the record, are hard to know and hard to like. Sean Nelson, the eloquent writer for the 33 1/3 series, in writing about Mitchell's Court and Spark called out Mitchell on Hissing for losing all sense of compassion and empathy - this is Mitchell at her most disdainful. Her opening image in "Mainstreet" is of "under neon a signs/ a girl was in bloom/ and a woman was fading/ in a suburban room." That might be the nicest comparison she makes on the record - she sees women as chained to Ethiopian walls, imagines Scarlett O'Hara wandering Times Square for porn, sees nagging wives ruining their husbands' lives, finds them unable to speak up to save their lives.

The truth is, as hard of an edge as these songs leave you with, I've never disliked them, not any of them, even "Edith and the Kingpin," which is, I think, a waste of a song. "Don't Interrupt The Sorrow" calls forth the history of women suffering and surviving only to be given the platitude "Bring that bottle over here and I'll pad your purse" - why not be angry? Its second half, too, has a perfect run - a man reminisces angrily on "Harry's House/ Centerpiece" and the result is experimental and beautiful. She dissects a bad local band in "The Boho Dance" rather dispicably as "just another hard time band/ with Negro affectations," but winds up really making a case for musicians needing to be true to who they are.

What keeps me coming back to Hissing is what has to be its strangest song - and Mitchell's strangest, for that matter. "Shadows And Light" was the first song I objected to on the record, and with its long, slow, drawn out keyboard as its only instrumentation, why wouldn't I? In her first mainstream negative review, Steven Holden of Rolling Stone wrote that the song sounded like "a long, solemn fart." But where the songs of Hissing are angry, "Shadows and Light" is lead by a synthesizer that accepts vicious dichotomies for what they are - stands in acceptance of them. "Hostage smiles on presidents, freedom scribbled on the subway," she sings to silence, and I have to think, to all things there are good and bad. We've given women - given ourselves - freedom and wound up bound to it. How do we reconcile the two? It's an effort to get there, but Hissing to me retains its fascination because it's, ultimately, just worth it.

Modern Guilt Beck

Beck has to be upset something fierce these days - the songs in Modern Guilt are pulled out of their straight malaise by dancy production of Danger Mouse, but there's not doubt of what he's feeling. "If I wake up and see my maker coming," he sings in the opening number, "Orphans," "We'll drag the streets with the baggage of longing." He drags the album with the baggage of longing - each song seems to be about how he no longer recognizes the world around him, and climaxes with Beck contemplating leaping into a volcano.

I should, in all honesty, truly identify with this record - I find myself baffled by modern culture constantly, and I think in 2006's magnificent The Information, Beck did just that - imagined a world with dead cellphones, drowned out by elevator music, and adrift with the strangeness of the world around him. The truth is, Beck's previous albums are the best reason to move forward with Modern Guilt anyway - knowing the winning streak he's been on. My theory with Beck has long been that 2002's classic Sea Change, full of such overwhelming sadness, freed Beck to make the music he wanted to - the far jauntier Guero and The Information along with Change are truly Beck's fullest, most inspiring work.

Modern Guilt is along that vein but is simply not as good because there is no movement - Beck's malaise traps you in the record and suffocates it with dance rhythms that feel mostly stapled on. A song like "Replica" makes great use with intensely overdone beats of creating a sonic landscape that seems impossible to penetrate, but most of the record does so without as much sense of consciousness.

But that consciousness still lingers and infects. The truth is I didn't care much about Beck when I was supposed to - Odelay and Midnite Vultures seemed like a lot of danc-y hoohah about nothing, and even when I liked a song I didn't care to go much further. Modern Guilt has so much to it, by contrast. "Orphans" is a great song, and so is "Volcano" (of that titular volcano Beck can't decide to jump into), and even at one note, a record about modern contempt and malaise is a stronger note than virtually all other albums in release. The truth is, the best thing of a record about malaise and contempt is that you feel it some yourself - you yearn for the release in songs like the crunchy rocker "Soul of A Man." That may be as effective as it is frustrating.